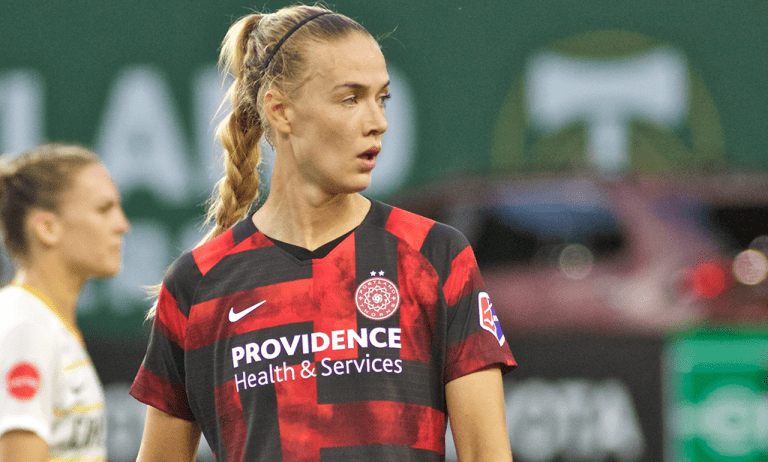

PORTLAND, Ore. – It’s early in West Portland, and although the mid-morning sun is still passing through the panes of her living room’s window, Dagný Brynjarsdóttir has turned to the shadows. It’s only for a moment – to remember what she once was – but in that moment her mind’s gone back two years, when she was only herself, to think about an old fear which, in day’s light, seems banal.

“I’m really scared of the dark,” she says, habitually placing that fear in the moment, even as she describes moving on. “When me and (former Portland Thorns teammate) Nadia (Nadim) would be roommates, and she would go to (her) national team when I was injured, I was scared to death of being by myself here, even though a lot of my teammates were alone.”

The layout of her apartment is from a brochure, designed to be blank - a canvas pulled over a frame for living. The space’s only fears are the ones you bring with you. But whereas in 2016 and 2017 Brynjarsdóttir provided that dread, 2019 casts her old frights as trivial.

“The first night after we got back, it was just me and Brynjar. I was like, ‘No.’” Fear no longer felt right.

“I just felt stronger, even though it was not like he was going to protect me. I guess because I had to be there for him, protecting him, I couldn’t let myself be scared. You just feel like a superwoman.”

Brynjar is an “easy kid,” Dagny admits. He’s just over a year old, now. Old enough to pull himself up on the furniture; to turn and laugh at what he’s done. He’s starting to collect a few words of his own, though he’s still figuring out their context. He opens the kitchen’s lowest cabinets, makes small piles of pans and pots in the middle of the floor. It’s too early to tell who he looks like more -- his mother or his father, Ómar – but if you look hard enough, you can see them both.

“People tell me he’s a dream baby,” she says, sitting on her living room’s couch, looking toward the hall where, in the space’s spare bedroom, Brynjar plays with a visiting aunt. The child’s laugh has been a constant through the walls. “He doesn’t cry much. He smiles a lot. He’s easy to take care of. He just makes me happier.”

He isn’t a cure, she reminds, quickly. There was nothing to cure. If anything, she’s reached a happiness she couldn’t envision, before.

“I was already happy,” she corrects, quickly, “smiley and everything. But he makes me even happier, and I appreciate everything way more.”

“I didn’t plan to get pregnant and be out from the game for so long, but it happened,” she says . “And it was the best thing, for me … I enjoy trainings more, playing the games. I enjoy being around my teammates. I enjoy every day with Brynjar and Ómar better. I’m not waiting for tomorrow.”

Brynjar Atli, as he’s called by his mom, arrived during Brynjarsdóttir’s time away from the Thorns, time she hadn’t anticipated when the team ended their 2017 National Women’s Soccer League season. That October, Brynjarsdóttir went from Portland’s championship-game win in Orlando to, six days later, one of Iceland’s most important games of their 2019 World Cup qualifying cycle – a match in Weisbaden against the favorites in their group, Germany. At the time, “soccer was number one, two and three” in her world.

“When Ómar and I started dating, I told him, ‘you have to be number two,’” she remembers - a concession, of sorts. Her future husband could break into her top three, but soccer still had to be one.

“’That’s just how it is,’” she told him. “I was this psycho soccer player who would be the first one out, last one in, train extra as much as I could. That’s probably why I would pick up stupid injuries. I would do too much all the time.”

That too much included four years at Florida State, where she was one of the best collegiate players in the country. She was a part of three regular-season Atlantic Coast Conference championships, one ACC tournament triumph, four College Cup appearances in the NCAA’s semifinals, and one national championship during her time as a Seminole. “If I look at my career since I was 15, 16 …” she remembers, “I won a title every single year except” the year she took off.

That includes her short time in Germany, where she played with Bayern Munich after electing to opt out of the NWSL College Draft in 2015. “’I want to compete with the best in Europe,’” she said to herself, then. “I know the coach, when I came in, didn’t plan to start me, but I earned my spot before the league restarted in February.” Bayern won the first of consecutive Frauen Bundesliga titles that spring.

Brynjarsdóttir still left Germany that summer, having discovered, “I just like the soccer better (in the U.S.)” After a spell in Iceland’s league allowed her to recover from some small injuries, Brynjarsdóttir signed with the Thorns, seeking an “environment (that) is going to make me better, as a player.”

Two years later, having won an NWSL Shield (as league regular-season winners) before that 2017 title, Brynjarsdóttir returned to Germany more accomplished, something that showed as she led her country against their World Cup-qualifying group’s favorites.

“It was probably one of the best games I’ve played with the national team, when I played against Germany,” she says. Her two goals and one assist led Iceland to a 3-2 upset over the world’s second-ranked team, temporarily putting them at the top of their qualifying group. “And then, we should have won Czech Republic away, right away, but we tied. We were just exhausted after the Germany game.”

By that point, Brynjarsdóttir had played matches in three countries (on two continents) in the span of 11 days, enough to test the limits of any professional. With hindsight, though, there was another reason for her fatigue.

“I didn’t know, at the time, I was five weeks pregnant. Maybe that’s why I was also really exhausted.”

The next time Iceland faced Germany, Brynjarsdóttir was in the stands. Her son had been born three months before, and by the time the group favorites arrived at the Laugardalsvöllur stadium, Brynjarsdóttir was 11 months removed from competitive play. At one time, soccer was her “one, two and three." Now, she was coming to grips with a new world.

“When you play soccer for so long, you think soccer is everything,” she says. “But it only took one baby to make me realize soccer isn’t everything. It’s just another life.”

For much of her pregnancy, she lived in denial, maintaining the same view she had of other players who’d become pregnant. “They would be like, ‘oh, it’s only seven months after my pregnancy. I’m not at my best yet,’” she remembers. “And I would say, ‘not at your best, yet? It’s seven months since you had a baby!’”

Pregnancy made her more open-minded; at least, she was more open-minded at first. “I read a lot of things online, trying to find interviews with athletes … It was hard to find something. Now that I’ve gone through this, (I know) every woman is different … It would be hard to get experience from someone else.”

She gave herself permission to continue as normal. Soccer was on hiatus, but she continued working out, doing so at a level that had always left her among the most physically fit players on her teams. “I sometimes trained too much when I was pregnant,” she admits. “I didn’t think it was a lot, because I was used to training like a professional athlete. I didn’t feel like I was training that much.”

At 35 weeks, she posted a picture on Instagram of her atop a rock mountain, flexing with her right arm as, in the background, the hill descended into fog. Two weeks later, she was in the hospital, giving birth, and three weeks after that, she looked like her former self, posting pictures while comfortably fitting into her pre-maternity clothes.

Within a month, Brynjarsdóttir was back on the field and training with one of her former clubs, Selfoss. It wasn't long before she understood why, for those players she had talked to before, returning from pregnancy took so long.

“I’m a physical player, and I guess when you’re missing that, when you’re coming back, it’s hard,” she admits. “In training, when players where running by me, I knew I was faster. Players were faster, stronger than me, and I knew I should be stronger. That was always tough.”

Pregnancy had increased her tolerance in one way, decreased it in another. The final sprints players endure at the end of practice? Mentally, those were easier, now. But that ease contrasted a connection with her body that made her more aware, and more cautious.

“Before I had Brynjar, if I had some injuries or some pain, I wouldn’t care,” she remembers, describing a ligament injury in her pelvis she carried forward from her pregnancy. “I would just play through it. But now that I’ve gone through all this, I respect my body way more. And I was like, ‘I’m not ready to play soccer with pain. I just want to play if I’m healthy.’”

Provided she wanted to play at all.

“I had this feeling that I didn’t care if I would play soccer again,” she said. “Soccer really was number one, two and three, but then I had this baby … I was like, I don’t know if I want to play soccer again.”

Brynjarsdóttir was still working through those doubts when Germany arrived in Reykjavík. As Iceland fell 2-0, Brynjarsdóttir was taken back to the feelings of "betrayal" she had when she left the squad, watching their World Cup chances disappear. "At least I could try to do my thing, try to win tackles, win battles in the air, finish my chances," if she were on the field, she says. "But you’re just there in the stands, hoping for the best. It was so hard.”

But she also admits “there were a lot of happy emotions" around that game. She was just finishing her longest spell at home since leaving for Florida State, and while she confesses there was “sometimes fear” at how her life was changing, the arrival of Brynjar had brought a new balance.

“With him being born, he’s made me calm down,” she says, describing how easy it was, in the past, to “get (her) up.”

“When we would have a tough loss, or I would play bad, I would think about it for days ... But now, after a game, when I'm at home, I see Brynjar, and I’m just happy …”

She can say that with comfort, now. Nine months ago, the new balance was more elusive, particularly given the standard she wanted to maintain on the field. While part of her mind was embracing a new life, part was still programmed to be the person who’d pushed herself to Tallahassee, Munich and Portland.

“That part of me was like, I didn’t want to play in Iceland, because I knew I was better than that,” she remembers. “I could be better. You always get better when you’re playing with better players. I wasn’t ready to play at the highest level, then have a baby and drop a level. I might as well, when I go back to playing, play at the highest level.”

Portland had stayed in touch throughout her time away, offering her a new contract before she chose to take time off, then making sure a new deal was in front of her when she decided to return. But she admits to being “a little scared, going away from small Iceland where we don’t really have any crime, I have family, everything around me. I take this little body, my little son, six months old, across the ocean to the U.S. I think I was a little scared with that.”

The Thorns’ contract sat with her for weeks. Her agent called, reminded her. She needed to send it back, signed. Brynjar was part of this, though. As was Ómar, and the life she’d crafted during her time back home.

Finally it was her physical therapist, back in Iceland, that assuaged her fear, offering her a reminder about her new world. The idea of stakes – what’s important, and permanent; what’s not – changes the moment you care for someone new.

“She told me, ‘if you go there, you can always go back home,’” Brynjarsdóttir remembers. “’Even though you sign a contract, I’m sure they’re not going to – if you’re unhappy; if it’s not working out – make you stay there’ …

“(Her physical therapist) was a 21-year-old single mom who went to Denmark for a year of school. I was like, ‘oh my God. You were so young. And with the baby?’ She was like, ‘yeah. And then I wanted to come home, so I just came home.’ She was like, ‘you can always do that.’

“That helped me. It’s not like I was going to go there and be stuck.”

There was no use putting everything on hold out of fear. Play, move, or don’t, the worst-case scenario would find her back in Iceland, with Ómar and Brynjar.

“And then, it was funny,” she says. “After I signed the contract and sent it in, I was happy with the decision. It was just hard to make the final decision.”

Five months after moving back to Portland, Brynjarsdóttir’s life has combined her worlds. She’s back where she was two years ago, going through the same beats as the rest of the Thorns. There’s time before training, time after training, all of which builds to games, and the occasional trip on the road.

Brynjarsdóttir’s time is just more structured. She likes it that way. Brynjar’s crib is just to the right of her bed, making him the first thing she sees in the morning. She spends their first hours playing with him, making him breakfast and lunch, putting him down for his nap before, when training comes, her old life returns.

“He’s the happiest in the morning, when he wakes up,” she says, smiling. “He just wakes up and is so happy to be awake and see you. Those parts are my favorite.”

Her least favorite is when she leaves. You can’t explain to a one-year-old why mommy has to go. But when she returns in four or five hours, the rest of the day is theirs. Reading. Baths. Time at her apartment complex’s pool, or walks around her neighborhood.

“He doesn’t cry all the time,” she assures. “I guess he just cries because he wants to go out with me. But it’s hard when I have to go out for training and I hear him crying.”

She didn’t realize it before, but this is the life she wanted. “When I was at Florida State, I never really pictured having a kid and playing, but I’m happy it happened,” she admits. “I love being a mom.”

There is conflict there; just not the one most people expect. We are used to athletes being single-minded about their careers and using that focus to drive them upward. When we think of mothers returning to their sports, we imagine a tension between what they were and what they are. For Brynjarsdóttir, though, the tension isn’t with the past. It’s with the future.

“How I put it when people ask me,” she says, “(is) if people tell me I could choose between playing soccer again or having another baby, I would always choose having another baby. It’s just the best thing. Obviously, it’s different, but I love it.”

She also knows she doesn’t have to choose. She’s only 27; she still has a need to play – the same need that took her back to Portland; and in the future that will come soon, she’ll be able to enjoy her other goals.

“My other two seasons (in Portland), I dreamt of winning a double,” she says, “but I haven’t done that yet. The first season, we won the Shield. My second season, we won the championship. Coming here again, I want to win a double.”

She also wants to leave a memory for Brynjar, as well everybody around her. “People I know, they would doubt me,” she remembers. “They were like, ‘do you think any teams would want you? Are you sure you’re going to be as good as you were before?’ Obviously, I would say ‘yes,’ but in the back of my head, I would say, ‘am I going to be as good as I was before?’”

Just past the half-way mark of the 2019 season, Brynjarsdóttir has started nine games, more than she did the season before her departure. Helping offset the World Cup absences of Lindsey Horan and Christine Sinclair, the injury to Angela Salem, Brynjarsdóttir leads the NWSL in duels won, even though international duty and her July wedding with Ómar have kept her away for two matches.

“I just want to make him proud and just be like ‘I can do it,’” she explains. “That’s what pushed me through, after I had him. I want to show myself, and I guess everyone else that I can do it. I can still be the same as I was before, maybe even better, even though I’m a mom.”

Four months’ play have eliminated any doubt. Brynjarsdóttir says she’s still not quite back to her former self, but she’s close. Close enough to lock down a regular spot in Portland’s midfield. Close enough to help guide the team to first place. She’s back playing for Iceland, too, leaving the 2021 European Championship as the country’s next big goal. Before then, though, there’s still the possibility of adding two more trophies to her time in Portland.

“I just know I signed for this year and next year,” she says, smiling, “and I will do (the double) before I leave.”

When she leaves, she’ll leave complete – perhaps more complete than she could have imagined before. Because although her departure two years ago came at one of her career’s highest moments, her life was ready for something more. The woman who ranked soccer one, two and three and trained until she couldn’t has found a more valuable honor.

“The biggest title is when I got Brynjar,” she says.

She’s no longer afraid of the dark. Any fear she carried for her former life left 14 months ago. Now, Dagny has Brynjar.