I spend a lot of time thinking about plus-minus data; far too much considering it’s unclear how relevant it is. Whether it’s places that statistic it’s commonly used, like hockey and basketball, or sports where it’s scarcely referenced, like soccer, I find myself jumping back and forth between two ideas. First, how your team does when you’re playing matters. It matters a lot. But second, given how many factors go into producing results in team sports, it will always be misleading to say something like, “that team scores less often with that player on the field, so they must not be playing well.” With any measurement, there’s always context to consider.

But I already feel like I’m getting ahead of myself. I should explain what a mean what I say “plus-minus data.”

Plus-minus is a stat that’s been kept in ice hockey since the 1950s. For each player, whenever their team scores a goal, they get a “plus;” when their team allows a goal, a “minus.” If you’re plus-three for the game, your team scored three more goals than it allowed when you were on the ice. If you’re minus-42 for the season, well, you’ve had a pretty tough year.

Plus-minus is becoming more prevalent around the National Basketball Association, where its most common use might be a statistic called net rating. It’s a step beyond the traditional plus-minus we see in hockey. Net Rating (on an individual basis) instead takes the number of points a team scores per 100 possessions when a player is on the floor, subtracts the same points allowed by that measure, and produces a “net” value. Among regular players last season, the Golden State Warriors’ Steph Curry had the league’s best net rating. His team outscored opponents by 13.7 points per 100 possessions when he was on the court.

Curry is one of the best players in the NBA, but even casual basketball fans might have questions about that number. For example, Curry played on the most talented team in the league. How much does his plus-minus data reflect his contributions compared to his teammates? (Probably a great deal.) How much is the figure about his team’s style of play, or their opposition? Perhaps his coach’s substitution patterns meant Curry spent a lot of time playing against opponents’ reserves.

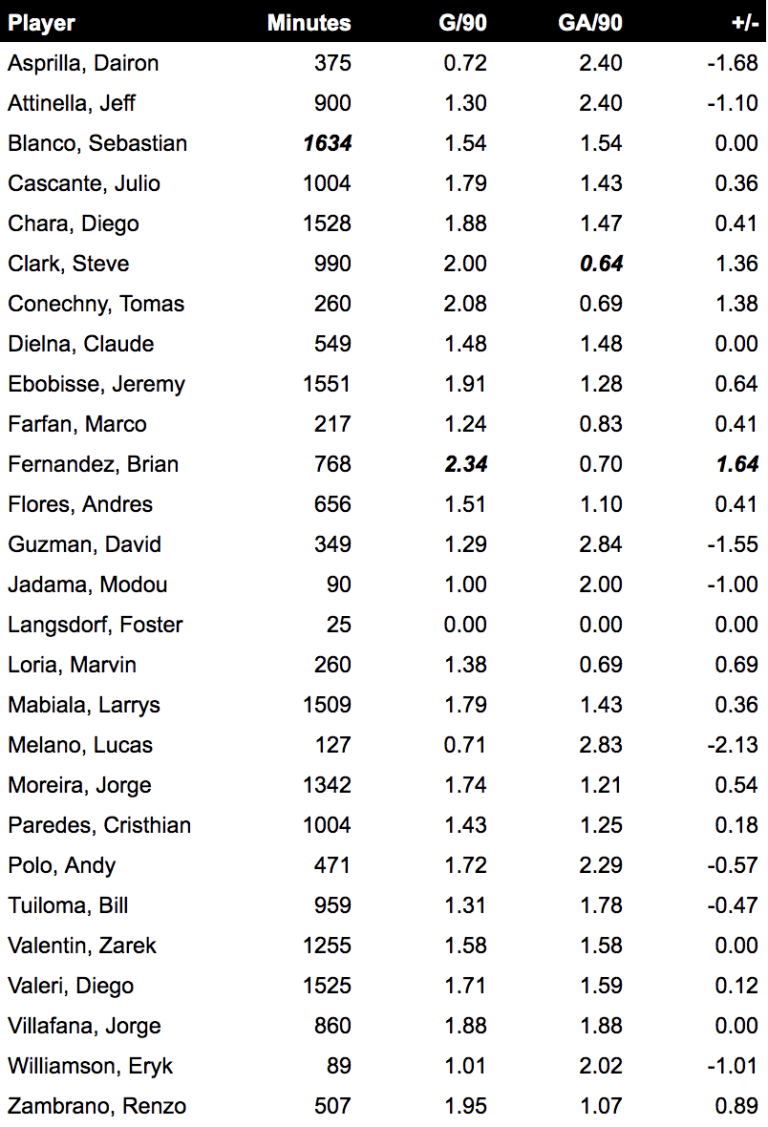

Those are these exact type of questions you should keep in mind as we return to the soccer realm and dive into some Portland Timbers data. For the first 21 games of this season, I’ve gone back and compiled a plus-minus for each player: how many goals Portland’s scored when he’s on the field; how many they’ve allowed; and how those two numbers compare to each other.

Given soccer is played 11-on-11, these figures only tell so much about an individual’s performance. They describe how the team has performed when he’s on the field, but they don’t tell us what (or how much) a player’s contributing (or detracting) from that performance.

(G/90 - Timbers goals per 90 minutes with player on the field; GA/90 - Timbers goals allowed per 90 minutes with player on the field; +- - G/90 - GA/90.)

It’s natural to look for the highs and the lows, but in doing so, you’re also seeking out the outliers. For example, the Timbers were +2.83 goals per 90 minutes when Lucas Melano was on the field, but he only played 127 minutes, this season. Even if plus-minus were valuable, that’s not enough to tell us anything useful.

Most other players with low numbers also lack playing time. Eryk Williamson, for example, saw the bulk of his minutes come in a rotated team during a 2-1 loss at Montreal, while Dairon Asprilla has seen just over four games’ action on the field.

That makes Brian Fernandez’s number a little more remarkable. His 768 minutes played isn’t a huge sample, but it’s enough to start seeing some regression to the mean (whatever the mean, here, is supposed to be). Yet the Timbers have still been 1.64 goals per 90 to the good when The Scorpion is in the lineup. To put that in perspective, Los Angeles FC has been +1.80 per 90 minutes this season.

Fernandez’s goals-for- and goals-allowed-per-90 columns give the picture of his play a little more depth. In terms of the attack, Portland is scoring 2.34 times per 90 when Fernandez is on the field, almost double the productively they’ve had without him (1.20). That’s a huge part of Fernandez’s plus-minus profile, but it’s also only half the equation. The team is allowing only 0.70 goals when he’s on the field; 1.93 with him off.

I list all that to set off a couple of alarms. First, the defensive numbers: How much is Fernandez really contributing defensively? The answer is certainly “more than nothing.” The team is pressing much better with him in the lineup, something that helps keep the ball further from goal and force turnovers. But is Fernandez’s defensive presence really worth 1.23 goals per game? It’s hard to imagine any player is worth that much.

Another other alarm, here, is about the schedule, as well as the general arc the Timbers have experienced this season. Before Fernandez arrived, the team was playing on the road with a defense that was performing far below its potential. By the time he arrived, the defense was already improving, while the schedule was about to turn toward a more balanced home-road ratio. How much Fernandez’s plus-minus data reflects those realities compared to his own contributions, it may be impossible to tell.

This may be why we don’t see data like this used more often. Without context, plus-minus can be more misleading than descriptive. Still, if you maintain perspective and don’t misuse it, plus-minus tells a story, particularly when you start directly comparing how a team does with a player on the field versus how it does without

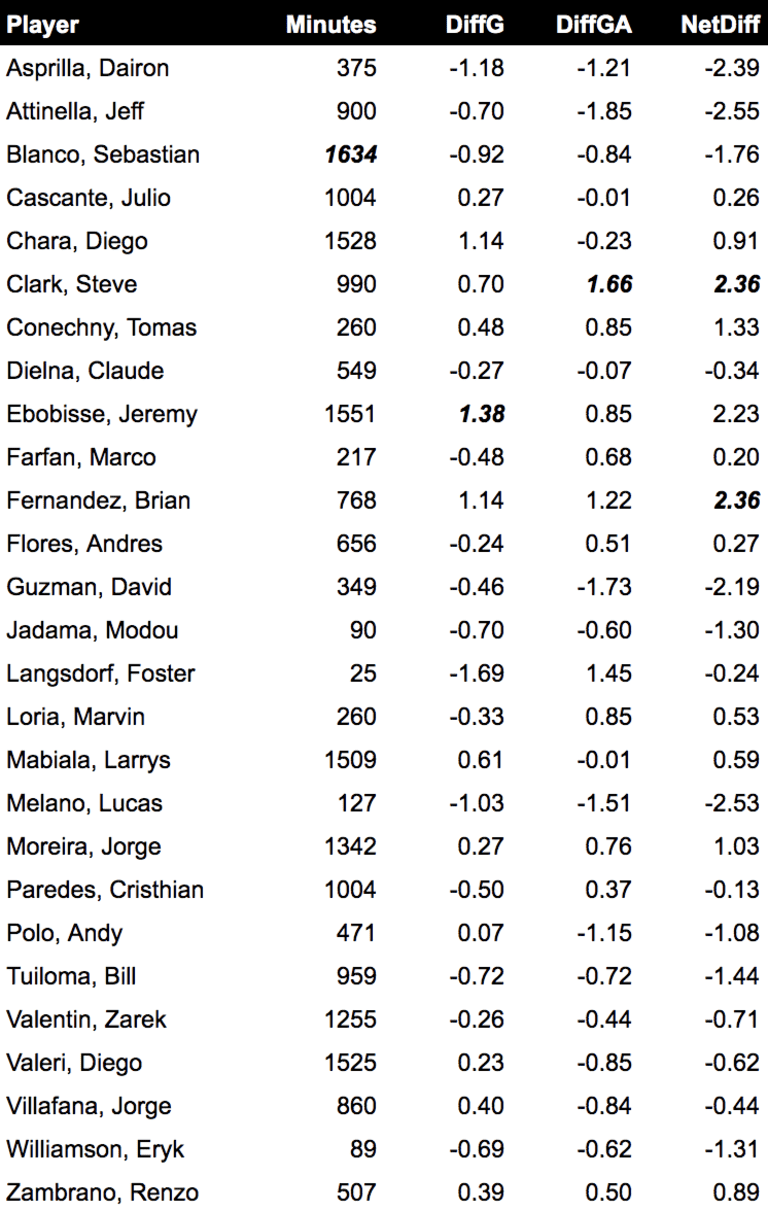

(DiffG - Difference in Timbers G/90 with player on vs. off the field; DiffGA - Difference in Timbers GA/90 with player off vs. on the field; NetDiff - DiffG + DiffGA.)

What does this mean? Let’s take Julio Cascante. When he’s on the field, Portland’s attack has scored 0.27 goals per 90 minutes more than when he’s out. The defense, however, is practically the same: only 0.01 goals per 90 worse. Overall, the Timbers have been a net 0.26 goals per 90 better when Cascante’s on the field.

By this measure, Fernandez still looks like a huge impact player, as does Steve Clark. They both have positive-2.36 ratings when they’re on the field. Jeremy Ebobisse (2.23) also has a high rating, while Sebastián Blanco’s is an example of our playing time caveat. The Timbers have only logged 256 minutes without Blanco this season, but in that time, they’ve scored 2.46 goals per 90 minutes. Is Portland really a team that would score 84 goals over the course of an MLS season? It’s more likely that Blanco’s numbers are a sample-size fluke.

Like I said, I spend a lot of time with these numbers, which makes it all the more frustrating that I don’t know if they’re useful. They’re greater descriptors, but there’s also a level where they feel like statistics for statistics’ sake. Sure, things like this help rebut statements like, hypothetically, “I don’t think the Timbers are better when Ebobisse’s on the field.” They have been, so far. But the number of potential explanations for that performance leaves plus-minus feeling like the beginning of a longer, more detailed journey. It feels like the start to a conversation, not a conclusion.

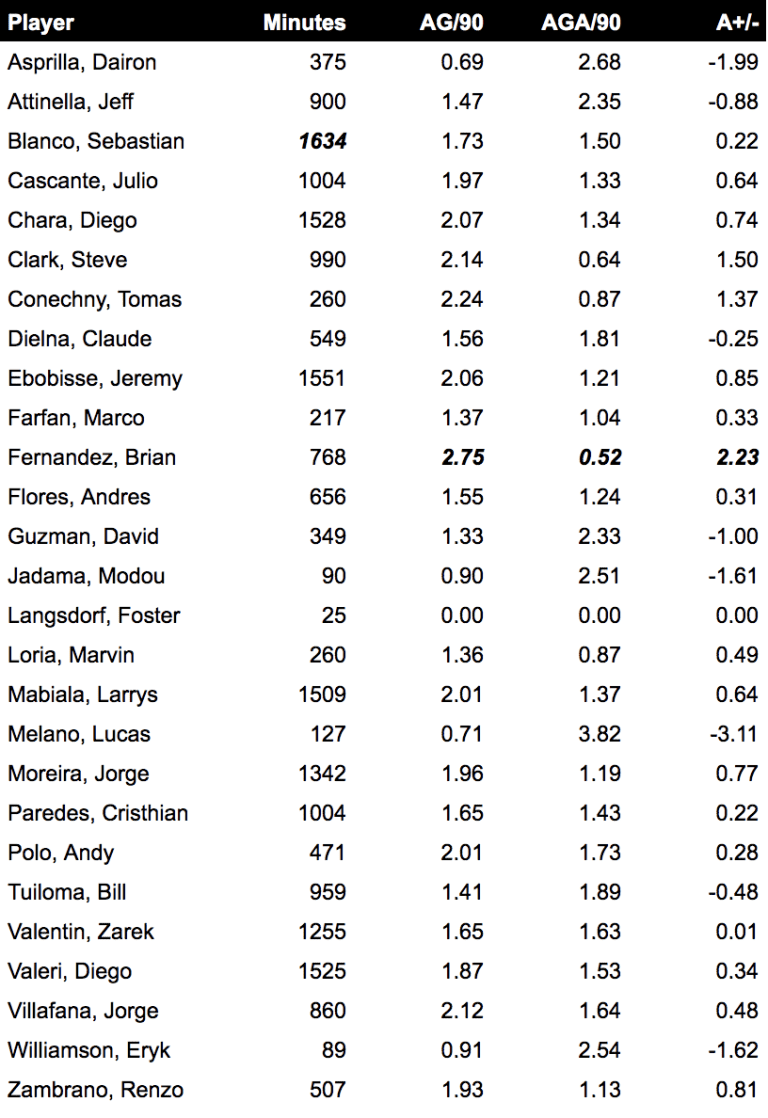

Still, I can’t help but try a next step – an attempt to bring a little more sense to something which, intuitively, feels like it should have value. For me, that next step is some basic opponent adjustment. After all, should scoring a goal against Los Angeles FC, the stingiest defense in Major League Soccer, really be considered on par with tallying against Colorado, the league’s second-most permissive defense?

Of course not, which is why for each the goals that go into determining one of these plus-minuses, I like to account for the opponent. It’s 43 percent harder to score a goal against LAFC, this year, than the average MLS opponent. If you’re looking at those scores in terms of assessing the value of the accomplishment, you could argue they’re worth 43 percent more. Likewise, it’s 35 percent easier to score on Colorado. When comparing those goals to others, their value should be adjusted downward.

(AG/90 - Opponent adjusted goals per 90 minutes for Timbers when player is on the field; AGA/90 - Opponent adjusted goals allowed per 90 minutes by Timbers when player is on the field; A+/- - adjusted plus-minus.)

Making those adjustments to every goal doesn’t meaningful change our list, but it does help address one of our qualms. Now, the measures take into account the quality of the opponent. As you can see, Fernandez sees a huge jump in his rating (compared to the first table) because, in having played LAFC (twice), New York FC and Philadelphia, he’s already faced a difficult schedule.

Even with all these attempts to massage, clean up, or find new views of this data, plus-minus in soccer seems to occupy the same, uncertain place it holds in basketball and hockey. It’s interesting, and it undoubtedly tells us a lot about the story. But it’s not the story itself, and in the context needed to bring clarity to these numbers, it feels better for fueling new questions than drawing conclusions.

Perhaps the most interesting question, here, is about the player we keep coming back to. In 768 minutes, the Timbers have maintained a near-LAFC-esque level with Brian Fernandez on the field. What are the odds they keep that up?

Notes: The minutes played reflected, above, may differ slightly from official stats because of my preference in how to log the minute of a player substitutions or dismissals; minutes played in stoppage time aren’t added, but probably should have been; all numbers include the Timbers’ three U.S. Open Cup games.